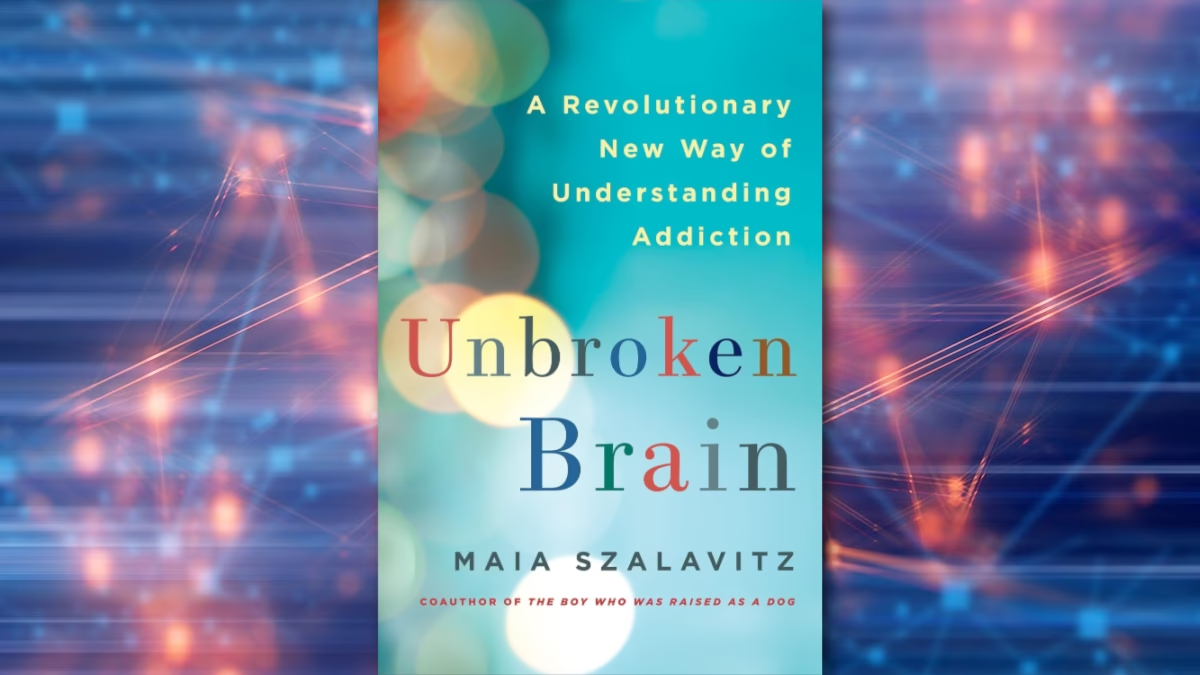

Maia Szalavitz’s “Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction” lives up to its title. It doesn’t simply reframe addiction; it helps readers understand why a new frame is necessary — and why changing the lens changes almost everything about how we help people recover. And its core message is powerful: When we stop seeing addiction as a moral failing or a “broken brain” and start seeing it as a learning and developmental disorder, the entire recovery landscape opens up.

Szalavitz blends the authority of a science journalist with the vulnerability of someone who has survived heroin and cocaine addiction. That dual identity drives the book’s clarity and compassion. She is not writing from the outside. She is writing as someone who has lived the desperation, the shame, the compulsive patterns, and the long climb out. Her neuroscience is rigorous, but her honesty is what gives the book weight.

She helps readers see addiction not as a defect, but as a set of coping strategies learned under extreme stress, pain, or emotional disconnection.

And that shift — from “brokenness” to “learning gone wrong” — matters. It doesn’t just change how we think about addiction. It changes how people recover.

Rather than accepting the disease concept, Szalavitz puts a new lens on addiction that does have scientific support. She states addiction shows the same patterns, mechanisms, and brain circuitry involved in other learning and developmental disorders — but in a harmful direction. Addiction tends to develop when we are young, and we learn to use chemicals as a coping mechanism, and the learning is too firm, too fast, too sticky.

The new model also broadens the range of what treatment can look like. If addiction is a learning disorder shaped by environment and trauma, then recovery requires more than “just stop” or “hit bottom.” It requires individualized approaches — harm reduction, medication-assisted treatment, trauma-informed therapy, community support, 12-step programs for some people but not all, and pathways that respect a person’s history rather than forcing them into a single mold.

Given that the book was published in 2016 and the author has a long-standing recovery, she seems out of touch with current recovery practices. Her book clearly points out that there are many ways to get into recovery, and it is not one-size-fits-all; however, she sells it in the context that the current “model” only recognizes one approach: a 12-step program. She also leans on harsh treatment methods that may have been in use decades ago, as she was entering recovery, that are acceptable today, except in the most harsh of treatment facilities.

Szalavitz also makes it clear that changing the lens changes policy. Seeing addiction as a learned survival behavior rather than a criminal choice shifts the conversation from punishment to support. It strengthens arguments for decriminalization, safe consumption sites, early intervention, and mental-health resources. It turns recovery from a private battle into a public responsibility.

But the most powerful impact of this lens shift is internal: the way it reshapes a person’s understanding of their own struggle. When someone stops believing “I’m broken” and starts thinking “I adapted to pain the only way I knew how,” self-compassion becomes possible. And self-compassion is fertile ground for change. Szalavitz emphasizes that addiction is not about bad people making bad choices. It’s about people who are overwhelmed using tools that eventually turn against them. That insight alone can transform recovery, especially for people drowning in guilt or self-hatred.

The book’s message is ultimately hopeful. Addiction is not destiny. It is not identity. It is not a death sentence. It is a human response to internal and external wounds — and understanding those wounds opens the door to better treatment, better support, and better outcomes.

If you want a book that offers a fresh perspective on addiction, Unbroken Brain is essential reading. It tears down outdated narratives and replaces them with a lens that sees people clearly — and gives them room to heal. My only criticism is that I believe the book could have been written without villainizing 12-Step programs and treatment methods, thereby showing how this model is radically different.

#QUITLIT Sobees Score: 4 out of 5

A STOIC SOBRIETY: Why “AA Doesn’t Work” Is the Laziest Argument in Recovery

A STOIC SOBRIETY: Step 12 and the Stoic Connection: Finding Purpose in Recovery

TSC LIBRARY: Welcome to The Sober Curator Library! This isn’t your average stack of books—we’re talking full-on story immersion, Audible binges, and reviews with personality. Browse our four go-to genres: #QUITLIT, Addiction Fiction, Self-Help, and NA Recipe Books. And if you’re collecting recovery reads like rare trading cards, check out our Amazon #QUITLIT list—almost 400 titles ready for your TBR. Grab your backpack, book nerd. We’re on a quest to read every last one.

A Disco Ball is Hundreds of Pieces of Broken Glass, Put Together to Make a Magical Ball of Light. You are NOT Broken, Friend. You are a DISCO BALL!

Resources Are Available

If you or someone you know is experiencing difficulties surrounding alcoholism, addiction, or mental illness, please reach out and ask for help. People everywhere can and want to help; you just have to know where to look. And continue to look until you find what works for you. Click here for a list of regional and national resources.